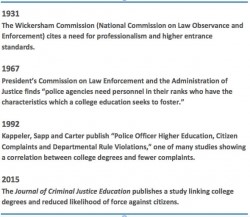

In 2015, the Journal of Criminal Justice Education published the most comprehensive on law enforcement and higher education to date. One major finding was that police officers with college degrees are less likely to use force against citizens.

More than 2,100 police officers were interviewed from police departments across the United States. Nearly 50 percent of those in the study had a college degree.

William Terrill, one of the co-authors of the study and a criminologist at Michigan State University believes degree programs that address social issues and incorporate topics like sociology and psychology train police to think more critically, which can change attitudes among police and the public.

“If you use less force on individuals, your police department is going to be viewed as more legitimate and trustworthy and you’re not going to have all the protests we’re having across the country,” he explained.

The research echoes numerous studies and recommendations going back to 1967 when the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice found that “police agencies need personnel in their ranks who have the characteristics which a college education seeks to foster.”

In 1992, the year of the Rodney King beating and the LA Riots, the “American Journal of Police published “Police Officer Higher Education, Citizen Complaints and Departmental Rule Violations.”

Following 120 officers over a 5-year period, the researchers found that individuals with a 4-year degree had a significantly lower rate of citizen complaints than those with some college but no degree. Officers with degrees also had significantly fewer complaints of rudeness than their peers.

Victor Kappeler, one of the study’s co-authors is now the dean of the EKU College of Justice and Safety. He believes it is vital to talk about education when we talk about police attitudes.

“We need critical thinkers, not just people who can react,” he explains.

Repeatedly, the profession agrees with him. In 2006, police chiefs from across the country, several of whom had required college credit for decades, contributed to an article in IACP’s The Police Chief magazine titled “College Education and Policing.” There were fewer disciplinary actions among college-educated officers, and the enhanced critical thinking skills and the ability to communicate with individuals from all walks of life led to higher levels of community engagement.

While incidents of militarization and police brutality often bring these issues to the forefront, Kappeler points out that the incidents themselves don’t tell as much as the broader social context surrounding them.

“Training for incidents alone is not sufficient problem solving. The incidents merely provide us with a catalyst,” notes Kappeler.

Police don’t cause these issues. They exist in the broader social context. It’s usually the resulting police action, often due to a lack of training, education and/or resources that causes us to pay attention.

Many of the same conditions that were present prior to the historic Watts riots in 1965 were replicated in Ferguson in 2014. Urban development and renewal in St. Louis displaced marginalized communities to the suburbs as residents of the suburbs moved back downtown. Police were then faced with situations for which they were not trained and challenges they had not previously encountered. On top of that, the police departments in the suburbs were less diverse, which likely contributed to additional issues.

Education can provide officers and civilians with a better understanding of the history influencing each event. There’s no doubt that every public incident alters our collective awareness. Yet, the fact that the same social strains continue to appear decade after decade tells us we still aren’t doing enough.